Rape is a crime of violence that modern, enlightened society has chosen to punish strenuously. Rape is also a sexual crime resulting in the victimization of women and children. During the Middle Ages, however, neither intent nor a sense of personal responsibility was attached to rape: women had few if any advocates, living in a society that marginalized them and preferring to see rape as the product of carnal intentions or “diabolical desire.” Historians researching available records and literature demonstrate that punishments were comparatively mild and in many instances women, unable to press their accusations, were arrested on charges of false appeal.

Women in the Early Middle Ages

Among the Germanic cultures encountered first by Romans and beyond the fourth century by Christian missionaries, rape was treated as theft within the parameters of the wergild system. Christianity did little to improve the status of women, often reinforcing notions that males were intrinsically superior to females.

Women were viewed as weaker creatures, the progeny of Eve, and therefore more prone to sin than the male. Sexuality was equated with procreation. Even among the Medieval nobility, rape – as defined under modern law, was punished mildly and seen as a “prelude” to marriage, impacting a woman’s honor more than her rights as a person, especially if forced sex was not accompanied by violence.

Reporting and Punishing Rape

Research demonstrates rape was not always reported and perpetrators represented all social classes. Historian John M. Carter, in his study of rape in Medieval England, writes that, “Clerics, or those claiming to be clerics, formed the largest percentage of rapists.” Carter’s study is confined to the 13th and 14th Century at a time English Common Law was still competing with separate Church courts. Ecclesiastical courts tended to treat an allegation of rape with less severity than evolving secular courts.

Punishment of rape, however, may have been impacted by social class as well as who comprised the legal authority. Carter, for example, concludes that, “…when a community was willing to kill or mutilate a man for rape, the crime was considered a felony; when the community was not willing to kill or mutilate a man for rape, the crime was considered less than a felony (possibly a trespass).” Additionally, poor women without means to appeal could be charged with a false accusation and further victimized through prison sentences.

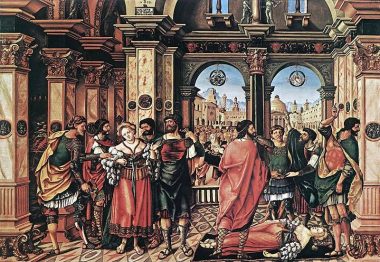

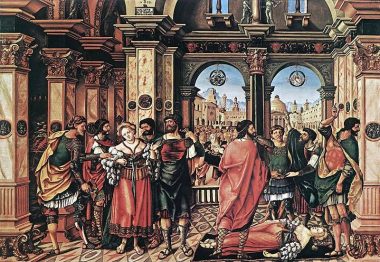

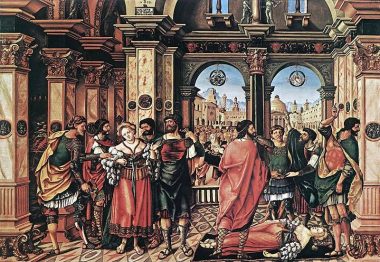

Punishments in Renaissance Venice

Guido Ruggiero, studying late 14th Century society in Venice, notes disparities in punishments relative to social class: “When rape struck down the social hierarchy, it could virtually disappear as a crime.” Ruggiero notes that the victimization of women was “merely an extension” of a society used to sexual exploitation, especially among women without social status. The absence of moralistic language and records of slight punishments for rape suggest that Renaissance society, at least as depicted in Venice, was not concerned with sexual violence against women and may have viewed the modern conclusions governing power and control in rape situations as a normal part of the male-female relationship.

The listing of punishments also suggests that rape was not treated seriously. According to Ruggiero’s study, the rape of a seven-year old child resulted, in one instance, in one year of jail. In another case, three men broke into a house, raped the owner’s wife, and took property. Despite premeditation (and, in modern terms conspiracy) and theft, each man received a year in jail.

Distinctions existed between married women, unmarried virgins, and children. In several documented cases, rape perpetrators judged guilty of violating an unmarried woman were obliged to pay a fine which would be used as a dowry once the girl married. Such examples, however, may not have applied to rural peasant women or the urban poor. Researchers note that few documents – if any, recount the plight of the poor, especially in the early Middle Ages.

Possible Impacts of a Patriarchal Society

The Middle Ages was a male-dominated society guided morally by a patriarchal hierarchy. This may help account for the marginalization of women, leading to sexual violence and rape. Historian Albrecht Classen argues that, “Understanding how this form of violence was viewed and dealt with…” enables contemporary society to better cope with the realities of rape and devise attitudes that afford protection in the future.

Although he does not conclude that male-dominated societies will produce more instances of sexual violence, Classen does note that patriarchal societies tend to “sweep…under the carpet” instances of rape and sexual violence. This view corroborates other studies of rape in the Middle Ages that link notions of gender to the non-equality of sexes.

References:

Danielle Regnier-Bohler, “Literary and Mystical Voices,” A History of Women: Silences of the Middle Ages, Christine Klapisch-Zuber, editor (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992)

John Marshall Carter, Rape in Medieval England: An Historical and Sociological Study (University Press of America, 1989)

Albrecht Classen, Sexual Violence and Rape in the Middle Ages: A Critical Discourse in Premodern Germany and European Literature (De Gruyter, 2011)

Frances and Joseph Gies, Women in the Middle Ages (Harper & Row, 1978)

Guido Ruggiero, The Boundaries of Eros: Sex Crime and Sexuality in Renaissance Venice (Oxford University Press, 1985)