Medieval monks and nuns lived by rules that demanded three vows: chastity, obedience and poverty. Problems arose with all three at times, and oft repeated regulations about careful segregation of the sexes, and even of youth and adults of the same sex within monasteries tell us that curbing physical desire was a challenge for many. Nuns were seen as particularly vulnerable, yet because religious women could not perform the sacraments (like mass and confession) for themselves, at least one ordained priest and often other men were required to serve female communities. The role of such men was to provide spiritual, sometimes intellectual guidance: to touch the souls and minds of their charges, but never their bodies. In many instances, this worked just as monastic superiors would have it, but a union of loftier ideals could lead to more worldly pleasures.

Taking monastic vows in the Middle Ages meant rejecting romantic and sexual relationships, but the meeting of ideal with reality could be elusive.

Goscelin of Saint-Bertin (c.1040-1114) and Eve of Wilton (c.1058-1120)

Goscelin, a monk from the French monastery of Saint-Bertin, was among the most learned and gifted writers of his time. Eve was a novice and nun of Wilton, a centre of women’s learning where Goscelin served as both chaplain and author. Goscelin also appears to have been Eve’s tutor, likely hired by her noble parents when she was still a child, and the affection with which he writes to her in the long autobiographical letter he called the Comforting Book is palpable. He tells of their long connection through books, church ceremonies, reciprocal acts of kindness, and mutual pleasure in each other’s company, but he also mourns their separation.

It seems that Eve decided to leave England and become a recluse on the continent–chose, that is, a more rigorous ascetic life that would have delighted many spiritual guides–and departed without consulting or saying farewell to Goscelin. In the early parts of the Book he expresses his shock and grief in terms so heartfelt that they are suggestive even in the context of heightened emotions characteristic of contemporary documents of spiritual friendship. Although there is nothing in what he writes that certainly indicates a sexual dimension to their relationship, many readers have detected hints of such intimacy and its dangers in both his language and Eve’s unannounced retreat.

Goscelin does come around as he writes, however, reassuming the role of spiritual guide and advising Eve on the reclusive life, but he also makes absolutely clear that peace of mind for him comes only via a conversion of their love. One of the primary comforts enacted by the allusive style of his Book is the transformation of their physical connection into a deeper and more permanent spiritual union in which their “two souls” will be rebuilt as “one.”

James Grenehalgh (c.1465/70-1530 ) and Joanna Sewell (professed 1500; died 1532)

Making one of two is an ideal James Grenehalgh, a monk of the Sheen charterhouse, realized in his own bookish way in his dealings with the Syon nun Joanna Sewell. Grenehalgh was among the Carthusian order’s professional bookmakers, specializing in the correction and conformity of Latin and English texts. Through Grenehalgh’s more personal annotations we learn of his relationship with Sewell. In his early printed copy of the Scale of Perfection, for instance, we find notes that guide Sewell’s reading, suggesting that Grenehalgh acted as her teacher and shared with her this book on the contemplative life.

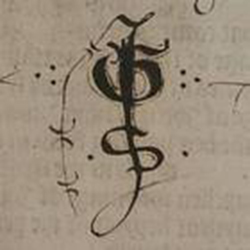

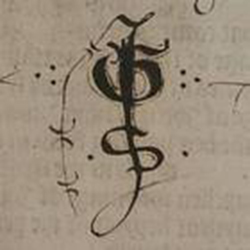

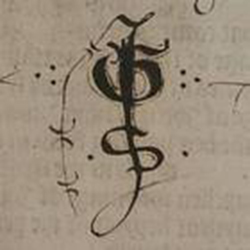

These notes are often marked by Sewell’s monogram “J.S.,” as is an inscription in Grenehalgh’s hand recording both her ownership of the volume and the date of her monastic profession. It is remarkable that Grenehalgh gave away such a precious tool of his trade–a book in which he recorded more corrections and variant readings than in any other surviving copy of the text. Even more exceptional is the way in which he intertwines his own initials with hers to form a shared “J.G.S.” monogram that unifies the two of them in a thoroughly scribal fashion.

Such signs of special affection for Sewell may explain why Grenehalgh was removed from his charter house near Syon in 1507 or 1508 and never allowed to return there. Perhaps it was their separation that led him to describe Sewell in one manuscript as a “recluse at Syon,” or perhaps it was her new circumstances. Syon nuns were not recluses, but failures of chastity could be punished by imprisonment, and choosing a solitary life within the convent may have sufficed.

Especially poignant is another of Grenehalgh’s notes in the same manuscript. “Forsake Sewell” it reads in such faint script that it seems an imperative its author was unwilling to acknowledge. It is a comment for a select audience, like some of the notes in the Scale he gave her that are positioned, sized and abbreviated so that only the most attentive of readers would notice them. One of these reports meeting “in the flesh” and was almost certainly written for Sewell’s eyes alone, revealing another role this book of the spiritual life may have played in the more physical existence of its two owners.

The Famous French Lovers, Abelard (1079-1142) and Heloise (c.1090/1100-1163/64)

With Abelard, a promising master at Paris’ university, and Heloise, the brilliant and learned young woman he tutored, their sexual relationship and its painful consequences became public knowledge. Chastity was expected of both a schoolmaster and an unmarried woman, but Abelard’s History of Calamities records the dangerous freedom they enjoyed under the rubric of education in the house of Heloise’s uncle. He also tells of their enthusiasm, confessing that they “left no stage of love untried.”

They did try to keep their affair a secret, but Heloise grew pregnant and had to be whisked away to Abelard’s family until their son Astrolabe was born. By Abelard’s report, Heloise’s uncle was enraged by her abduction, yet agreed to their marrying, even in secret as Abelard requested to protect his career. He did not keep the secret, however, and when relations between the three disintegrated, Abelard disguised Heloise in monastic robes and hid her at a convent. Her uncle misinterpreted his intentions and retaliated by hiring men to castrate Abelard in his sleep.

He survived, but as a changed man. He decided to take monastic vows and insisted that Heloise do the same. She complied, but admitted in a later letter that love for him, not religious conviction, led her to the cloister. It is only one of the ways in which her opinions differed from his. She also resisted the secret marriage, knowing that her uncle would not be so easily appeased, and years later she still refused to accept Abelard’s understanding of the mutilation as “a stroke of justice” in one body that initiated “the healing of two souls.”

Instead she frankly admits both to feelings of resentment toward a divinity who would punish them unjustly once they were married, and continuing desire for the physical pleasures she remembers with delight. Rather than the “crown” of salvation Abelard would win for her, Heloise is aware of her hypocrisy as a successful abbess, and happy to settle for any “corner of heaven.” As the only one among these three women whose own voice we hear, Heloise provides us with a medieval perspective on human love and sexuality very different from that of her male partner. Not the fruit she might have imagined perhaps, but sweet upon the tongue all the same.

Sources

- Hollis, Stephanie, ed. 2004. Writing the Wilton Women: Goscelin’s Legend of Edith and Liber confortatorius. Turnhout.

- Levitan, William, ed. 2007. Abelard and Heloise: the Letters and Other Writings. Indianapolis.

- Olson, Linda. 2011. “‘Swete Cordyall’ of ‘Lytterature’: Some Middle English Manuscripts from the Cloister.” In Opening Up Middle English Manuscript Studies: Literary and Visual Approaches, ed. Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, Linda Olson and Maidie Hilmo, Ch.6. New York.

Article published first time by Linda Olson on: April, 2011