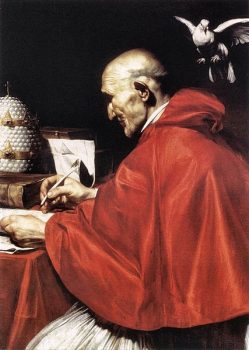

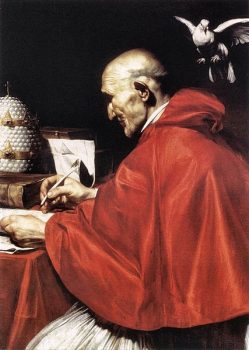

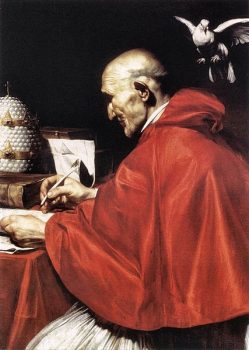

Gregory the Great became pope in AD 590 at a time the western Church was desperate for a strong, wise leader. Under Pope Gregory I, the Catholic Church successfully promoted extensive missionary activity among the barbarian tribes of Europe, notably in England. By refocusing efforts geared toward the West, this realist pope turned the papacy into a formidable spiritual and political power precisely at a time the Byzantines in the East were growing more distant. Gregory the Great has been rightly compared to Ambrose and Benedict and called the “father of Christ’s family.”

Pope Gregory’s Qualifications help Fashion the Medieval Papacy

Born into wealth and an illustrious Roman family, Gregory entered civil service, becoming the Prefect of Rome at a time the Lombards were pillaging Italy. Gregory led the defense of Rome and the care for impoverished Romans, a task he continued as pope. Pope Gregory I is characterized as a superb administrator and pastor whose endeavors included extensive missionary activity among Europe’s pagan tribes. Gregory was sent to Constantinople as an envoy. It was a time Greek had replaced Latin and the Byzantine emperors believed they had the power to influence Christian church belief as well as appoint bishops and patriarchs.

Although the Byzantines still controlled parts of Italy, such as at Ravenna, the western Latin Church was in the process of charting a new course that no longer looked to Constantinople. As pope, Gregory recognized Constantinople’s tenuous position in Italy where the Catholic Church was the largest landholder.

The Papacy’s Link to the Old Roman Empire

The pathway from old Rome to the emerging European Middle Ages was kept by the papacy when all other institutions had failed. Gregory correctly sensed that the future of the church lay not in Constantinople, but with the barbarian tribes of Western Europe.

As barbarian hordes entered the former Roman provinces, only the Church through the bishops represented both civil and spiritual control. The Church became the binding force that confronted paganism while maintaining social stability.

Through the efforts of monasteries, notably those founded by Benedict, education continued and the link to the past was preserved. Gregory the Great relied heavily on these Benedictine monasteries and utilized the monks to convert the barbarians.

Missionary Activity under Pope Gregory the Great

Gregory’s missionary zeal among the Franks and the Anglo-Saxons in England was the first step in a process that would culminate with Charlemagne’s coronation in Rome on Christmas Day in AD 800.

At the same time Benedictine monks led by Augustine were sent to Kent to convert the pagan King Ethelbert and his people, other missionaries from Scotland were moving south into England as well the Baltic regions of Northern Europe. It was here that Boniface, the “Apostle to the Germans,” began a conversion process that opened doors to the eventual conversion of Poles and Czechs.

Christianity and Paganism in the Early Middle Ages

Although Gregory I rooted out paganism and attempted to suppress local superstitious practices as in Sicily, he was more circumspect among the Angles in England. In a letter to Augustine, Gregory ordered the destruction of idols but not the pagan temples. “The temples should be sprinkled with holy water,” he wrote, placing altars and relics in the sanctuaries.

In the same letter, Gregory condoned the on-going festivals associated with pagan rituals but shrewdly suggested that their meaning be tied to “good fellowship,” consuming the food not as sacrifices to demons, but “for the glory of God.”

Similarly, writing to Bishop Leander in Spain, Gregory condoned the traditional practice of single immersion during Baptism to distinguish it from triple immersion, which was practiced by the heretical Arians.

Early Church Preoccupation with the End of the World

Gregory, like many early Christian leaders, believed that the end of the world was approaching. This anticipation served as another motive for missionary activity. It was God’s will and plan that as many pagans as possible be brought into God’s kingdom.

Gregory’s sermons or homilies are filled with challenges to live lives of moral goodness. His homilies and superb administrative leadership skills legitimize comparisons to Ambrose, bishop of Milan, the earlier cleric who had converted Augustine of Hippo.

Pope Gregory the Great Teaches Pastoral Care

Gregory imposed a standard of Christian ethics and morals on all levels of clerical activity. In Pastoral Care, he writes, “Many wise teachers also fight with their behavior against the spiritual precepts which they teach with words, when they live in one way and teach in another.” Thus, the bishop was admonished to be a shepherd in his diocese and the priest the spiritual caretaker of his flock. For Gregory, “…every evil can be neutralized with good…”

Gregory the Great Contributes to the Coming of the Low Middle Ages

History is filled with transitional figures, men and women whose greatness in the annals of history rest with their selfless abilities to preserve all that is good and meaningful from the past while charting a path toward a stable and just future. Gregory the Great was such a figure.

His efforts helped to propel the papacy into a position of leadership, sorely needed in the absence of Roman imperium and the waning influence of Constantinople. These trends led to the papal monarchy and the formation of different institutional models from the Byzantine East. Unlike future popes, however, Gregory’s motives were dictated by the sincere conclusion that personal or institutional power must never take the place of devotion to God and the cause of Christ.

Sources:

- W. H. C. Frend, The Rise of Christianity (Fortress Press, 1984)

- Pope St. Gregory the Great, “Pastoral Care,” The Catholic Tradition, The Church, Volume I (McGrath Publishing Company, 1979)

- Gustav Schneurer, Church and Culture in the Middle Ages, Volume I, 350-814, Translated by George J. Undreiner (St. Anthony Guild Press, 1956)