Over 50 biographies and numerous books on individual aspects of Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890) life now exist. Critics described him as a charlatan and a fraud. His admirers, on the other hand, describe him as the pioneer of archaeological science, the genius researcher and the generous millionaire. However, the diverse written and evidence about his life does not help in the search for the real Schliemann. On the contrary, some biographers tried to manipulate within his memories from his letters and diaries. On the other hand, some critics considered the biography of Heinrich Schliemann as fake.

Archaeologist Wolfgang Schindler in his article “An Archaeologist on the Schliemann Controversy” summed the facts about Schliemann contradictory data from his diary: “A decisive new impetus for a realistic conception of the context in which Schliemann constructed his understanding of himself began with the now legendary midnight lecture in the pastor’s house in Neubukow on 6 January 1972, the 150th birthday of Heinrich Schliemann. It was given by Professor W. M. Calder III, a leading pioneer of the new Schliemann research….What was most striking was the fact that in Rostock there existed no dissertation written in ancient Greek with which in 1869 Schliemann could have earned his doctorate…There was only a vita of about eight pages written in Greek, Latin and French…Calder proved that the granting of Schliemann’s U.S. citizenship did not occur in 1850 but in 1869. Further, the visit to President Fillmore at the White House 21 February 1851 in fact never took place but was made up by Schliemann and inserted into his diary.” Besides that, this was not only controversy about Schliemann biography.

Heinrich Schliemann’s business career

From the most common biographical facts Schliemann was born 1822 in German town Neubukow as a son of Ernst Schliemann who was a pure pastor and Schliemann grew up in the Mecklenburg village of Ankershagen. Schliemann’s mother Luise Therese Sophie died when he was a nine-year-old, and one year later his father dismissed from his duty because of immoral life. Schliemann spends the rest of school time with his relatives, and then he completed a commercial apprenticeship in Fürstenberg. After spending around five hardworking years in Fürstenberg Schliemann health worsened.

Then in 1841 he decided to leave his job and went to Hamburg. In Hamburg, he found a new job in a ship named Dorothea but during the travel to South America he experienced a shipwreck. As a survivor of the shipwreck, Schliemann with other survivors managed to reach the coast of the Netherlands. Schliemann later found a job at the international trading house Schröder and soon he become indispensable because he had talent for business and gift to learn many languages. Until his death, he learned around 20 languages. In 1847 he moved to Russia, firstly as a clerk of the trading house Schröder, but later as a merchant on his own business. Three years later in 1850, Schliemann learned the death of his brother in California and he immediately went to America. At the beginning of the 1851 Schliemann started a business with a new bank in Sacramento, and soon he doubled his wealth, but in April 1852, he sold business and returned to Russia. In Russia, he married Ekaterina Lyschin and during the Crimean War 1854–1856 his wealth was further increased because he was a distributor of the military equipment. During a trip around the world, his childhood dream comes again: Schliemann wants to become an archaeologist and discover the historical scenes from Homer’s epic poems “Iliad” and “Odyssey”.

Schliemann as archaeologist

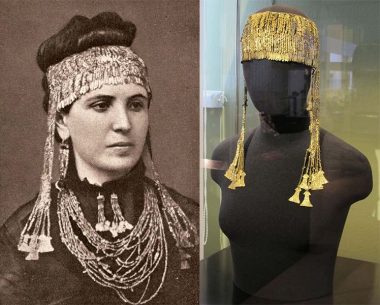

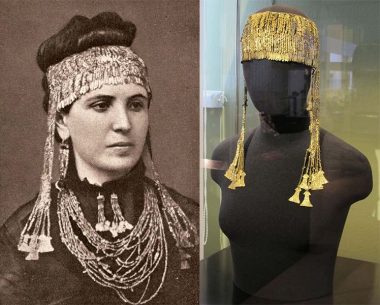

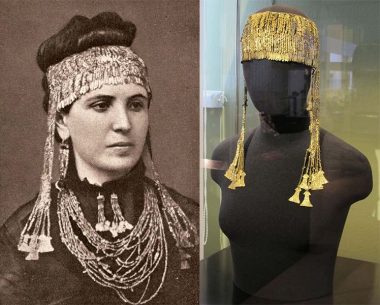

Schliemann’s interested in archeology and history begins during his childhood. On Christmas Day, 1829 from his father he got a Christmas Gift a copy of book “Die Weltgeschichte für Kinder” (History of the World for children) by the author Georg Ludwig Jerrer. Schliemann started his studies about archeology at the Sorbonne in 1866, but this lasted only one month. Two years later in 1868 at The Collège de France he took courses about geography, ethnography and archeology. In 1869 Schliemann ends his unfortunate Russian marriage and immediately marries a thirty-year younger Greek Sophia Engastromenos (1852–1932). By the Schliemann suggestions, their two children was named exactly the same as actors of the Trojan War, Andromache and Agamemnon.

Francesco Bini (Sailko) under license CC BY-SA 3.0

After finishing courses at the Collège de France Schliemann began his intensive engagement in archeology especially when pope invited him in Rome to participate in excavations of the Palatine Hill and around the Naples. During the excavations at the Pompeii site he met another pioneer or archeology Giuseppe Fiorelli. In 1870 Schliemann traveled to Troada (Biga Peninsula) and one year later within around 80 workers started to excavate possible archaeological sites of the ancient Troy. On Hisarlik Hill he discovered the ruins, the remains of former settlements and city at the several layers of to remain archaeological materials. He quickly announced that he had discovered the castle of the Trojan king of Priam. The news was spread in Europe, and scientists harshly attacked this theory, blaming Schliemann about “this nonsense”. Then he decided to stop further research. But the day before the leaving of this archaeological site, Schliemann accidentally saw how the sun’s light reflecting of some kind of object. It turned out to be just one piece of the many silver and gold items that he had discovered later. He was confident that he had found Priam’s treasury and jewels of the Helen of Troy. The news of this discovery caused quite the opposite public reaction compare to previous because this time Heinrich Schliemann received a deep respect. Schliemann published his discovery in his Trojanische Altertümer (or Trojan Antiquities) 1874. Because he was suspicious what will happened later with artefact’s (especially golden) found in Troy, Schliemann smuggled the treasure out of Ottoman Empire.

After that, he continued his archaeological excavations at the site Orchomenus (Boeotia) in 1875 and year later (1876) in north-eastern Peloponnese at Mycenae. Later in 1879 and 1882/3 Schliemann also started excavation at Troy. During the excavations, critics had usually blame him for failing to give right conclusions about the proper date of certain artifacts and his many conclusions were without relevant arguments. Also some critics says that his method of digging was brutal because he destroyed some evidence in order to find more interesting artifact’s. Although he was not in the right sense an educated archaeologist, Schliemann awarded PhD in 1869 by the University of Rostock in absentia (without his presence). Schliemann died on 26 December 1890 in Naples, and his body was buried in Athens Cemetery.

References:

- W. M. Calder HI, “Schliemann on Schliemann: A Study in the Use of Sources,” GRBS 13 (1972), 335-53;

- Wolfgang Schindler, “An Archaeologist on the Schliemann Controversy”, Illinois Classical Studies, Vol. 17, No. 1, Illinois 1992, 135-15;

- Finding the Walls of Troy: Frank Calvert and Heinrich Schliemann at Hisarlik, California 1999.