Hadrian’s long second century rule, from CE 117 to 138, signifies a Roman Golden Age, a period of prosperity and peace managed astutely by a statesman-like emperor who believed in peace through strength but also accomplished what one poet and scholar has called a “Greek renaissance.” It was Hadrian’s Hellenophilia, seen through his numerous journeys in the East and his public affair with the Bithynian boy Antinous, which circumvented Roman views of a decadent Greece and channeled a new burst of energy evident in stone: the many monuments, statues, aqueducts, roads, temples, and cities built to commemorate his divine greatness. According to Julia Balbilla, a contemporary member of his traveling court in November 130, power was exemplified in stone.

Multi-Faceted Emperor

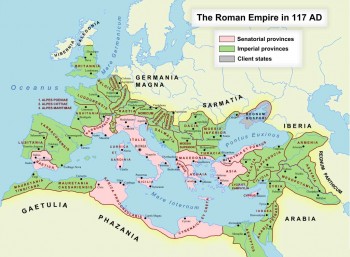

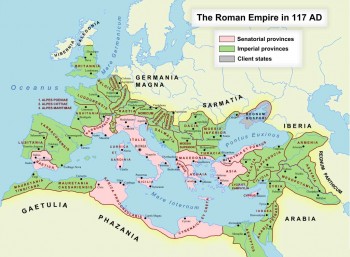

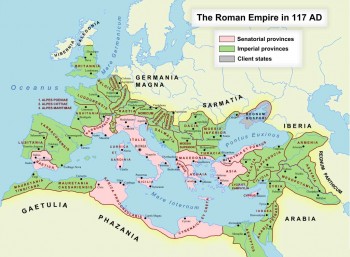

He was a complex man, an “internationalist who pursued the advantages of peace within his borders…” When Trajan the warrior died in 117, Hadrian was in Syria, consolidating his power within the military. Hadrian stabilized Rome’s borders, traveling through its many sections and leaving monuments to commemorate his visit. England’s seventy-four mile-long wall, named in his honor, marked the imperial limits in the West.

Hadrian wrote poetry, commissioned temples and palaces, and synthesized Greek culture with Roman discipline. He was the first emperor to be bearded. Contemporaries note that he was moody, flying into unexpected rages, banishing courtiers whose thoughtless comments or writings went beyond the point of wit. And then there was Antinous, his favorite, his pet, his lover.

The Antinous Affair

Hadrian first saw the Bithynian youth while visiting Asia Minor. Antinous might have been remembered as any one of a dozen favorites had it not been for his “accidental” death in Egypt. According to Julia Balbilla, a noblewoman in attendance to the neglected empress Sabina, “…one minute he was dancing and singing with wine playing the part of his muse, the next, he was a god blazing in the firmament.”

Antinous was Hadrian’s young sexual partner. While sailing up the Nile, the young man fell overboard and drowned, giving rise to numerous theories about his death. Was he murdered either by Hadrian himself or those around the emperor seeking to protect him? Was the death of Antinous a sacrifice? Hadrian’s grief, however, was long and deep. He built a city on the Nile to honor the boy and commissioned statuary that was spread throughout the empire. He elevated Antinous to the status of god and linked him to a new star that appeared over Egypt. According to Elizabeth Speller, “Antinous was not just the last pagan god, he was the inspiration of the last glorious florescence of classical art.”

Hadrian’s Motives for Traveling the Empire

Hadrian began his 21-year rule over the Roman Empire in AD 117, but spent half of his reign outside of Rome, visiting the territories. He has been called the “tourist emperor” and the “restless emperor” as a result of his numerous journeys. Yet far from being just a tourist, although, according to Michael Grant, curiosity was certainly a motivation, his sojourns strengthened the Imperial frontiers and attempted to establish more equitable relationships with far-flung provincial centers.

Tony Perrottet, retracing the tourist journeys of Pax Romana Romans including Hadrian, writes that the emperor himself said that he wanted “to see with his own eyes all he had read of in any part.” The highly literate and culturally-inclined emperor included many of the “popular” sites that wealthy Romans included on tour itineraries: Egypt and the Nile, Troy, Ephesus, Athens, and Delphi.

Everywhere he went, Hadrian built temples, fortifications, aqueducts, and other monuments to his glory. His visit to Britain resulted in “Hadrian’s Wall,” a 74 mile-long fortification to protect the province from barbarian attacks. According to Lionel Casson, “Everywhere we turn we see the touch of his hand…”

At the same time, Hadrian wanted to strengthen the Imperial frontiers, filling garrisons with provincial troops, the harbinger of a time when almost all of Rome’s legions would be comprised of non-Roman troops. This coincided with his keen sense of military preparedness. Perhaps his greatest motive and legacy was the development of a new perspective of the empire which can only come from personal observation and interaction with provincial peoples.

Michael Grant refers to this, writing that Hadrian viewed the territories “no longer as a collection of conquered provinces, but as a commonwealth in which each individual province and nation possessed its own proud identity.” Ironically, although the empire would remain at peace until the frontiers began to unravel during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, Hadrian’s policies may have resulted in the growth of more autonomous, self-sufficient entities, ultimately weakening the entire fabric of Imperial control.

Death on the Nile

It was in Egypt that Hadrian lost the youth who had become his obsession. His relationship with the boy Antinous, resulting from Hadrian’s proclivity toward homosexuality, ended abruptly when the young man drowned in the Nile during Hadrian’s visit to Memnon in AD 130. Although scholars cite suicide as a motive (those who died in the Nile achieved immortality through Osiris, according to Perrottet), other suggest more clandestine causes designed to protect the emperor, who was ill at the time, from scandal.

Another motive suggests that Antinous gave his life so that Hadrian would recover from illness. The death, however, deeply affected Hadrian who commissioned dozens of sculptures of the youth and had him deified. Near the spot where Antinous had died, the emperor erected a temple.

The Legacy of Hadrian’s Travels and Final Years in Rome

Many of Hadrian’s monuments and public works projects still exist today, including the Pantheon in Rome. His personal interest in the workings of the empire ensure continued peace and stability, along with significant internal and bureaucratic reforms, not the least of which includes an orderly imperial succession.

Lionel Casson argues that, “The Roman Empire was the longest-lived in history; Octavian Augustus created it, but he must share with Hadrian the credit for its longevity.”

Hadrian left Egypt, returning to Rome, after detouring through Asia Minor and Greece. The latter part of his reign was spent putting down the bar Kokhba revolt in Judea and obliterating the Jews in the process. The revolt was costly and Hadrian was forced to fight a guerrilla campaign.

Although much literature of the period is lost, including Hadrian’s autobiography, surviving accounts portray an ailing emperor whose symptoms suggest heart or liver disease. He resided at Tivoli, a vast rural estate archaeologists compare to a small city. Before he died, he ensured the peaceful succession bringing Antoninus Pius followed by Marcus Aurelius to the imperial throne. Rome would be at peace until the rise of Commodus.

Hadrian’s legacy was a continuation of the peace of Rome, visualized, in part, by the monuments raised by the emperor. The Pantheon in Rome is still in use as a Christian church. It is difficult to wander the ancient and disappearing neighborhoods of the second century in the eastern Mediterranean and not find a marker pointing to Hadrian.

Sources:

- Lionel Casson, Everyday Life in Ancient Rome (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998) see chapter 13.

- Michael Grant, History of Rome (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978).

- Tony Perrottet, Route 66 A.D. On the Trail of Ancient Roman Tourists (New York: Random House, 2002).

- Anna G. Edmonds, Turkey’s Religious Sites (Istanbul: Damko, 1998)

- Robert B. Jackson, At Empire’s Edge: Exploring Rome’s Egyptian Frontier (Yale University Press, 2002)

- Elizabeth Speller, Following Hadrian: A Second-Century Journey through the Roman Empire (Oxford University Press, 2003)