From the reconnaissance of Julius Caesar in 55 BC, to what is called the “Saxon Advent” in 49 AD, the lands of England, Scotland and Wales increasingly came under the sway of Rome. From the formal invasion of the Emperor Claudius in 44 AD. until the “Rescript of Honorius” four centuries later, Britannia was one of Rome’s most remote, yet vital, provinces, changing during that half-millennium past the recognition of Caesar’s soldiers in their first sight of the island. For discussion of all aspects of Rome’s impact and legacy upon Britannia and what would become Great Britain.

Britannia was a great unknown to the average Roman. Few knew much of it, and most had only a hazy notion of the island’s location and geography. As an example, when circa 200 CE and after almost 150 years as a Roman province the educated Roman Gaius Iulius Solinus wrote a geography (admittedly highly plagiarized), he could write of Britain as being ‘another world’ bordering on islands notable for the ‘inhuman and savage practices of the inhabitants’.

Britain remained neglected by the Mediterranean world during the time Rome was building her republic. This changed between 125 and 121 BC when British tin was transported to Massilia via a depot called Corbilo, on the Loire estuary, and hence overland — even though, according to Strabo, ‘no-one of all the Massiliotes… was able when questioned by Scipio [Africanus] to tell him anything worth recording about Britain’.

Gaius Julius Caesar first came to Britain in 55 BC. This was the first of his two invasions of the island. Caesar became interested in the island of Britain partly because the British Celts had been assisting their mainland brethren in resisting the Roman advance into Gaul, and partly because of the lure of the wealth the ‘tin islands’ possessed.

The Romans were initially disconcerted by the agile mobility of the British chariots, and both times the Channel tides wrecked large parts of the Roman fleet, preventing Caesar from following up on his land victories. During the second invasion Cassivellaunus, who ruled most of southeast Britain, was defeated and the tribe of the Trinovantes accepted Roman protection. Hostages were given to Caesar and taxes assigned, but any follow up invasion of Britannia was permanently delayed by the Gallic revolt the next years, followed by the Roman civil war, and finally by the assassination of Caesar and a further bought of civil war. However over the next few decades many British nobles began to expect an eventual successful Roman conquest. Almost a century later, when in 43 CE Roman forces under Claudius did invade, they were able to call upon a large amount of reliable information from merchants and exiled nobles.

In 43 CE an army of 40,000 men under Aulus Plautius left Boulogne for Britain. The army consisted of four legions: the IInd Augusta, IXth Hispania, XIVth Gemina, and XXth Valeria, about 20,000 men total. The remainder were auxiliary units of 500 and 1000 men; this ratio was usual for Roman armies. Some of these forces disembarked at Rutupiae (Richbourough) according to archaeological evidence, but the fortified beach-head defenses are not large enough for the entire army and some must have landed elsewhere. This was most likely the harbors in the Chichester-Portsmouth-Southampton area, where there was pro-Roman support and the distance to the main enemy base at Camulodunum (Colchester) was short.

The successive governors after Aulus Plautius slowly brought much of Britannia under Roman control. By 49 CE a new colonia for retired veterans had begun to rise at Camulodunum, and the 50s and 60s saw a gradual acceptance of Roman values by the traditional British aristocracy. Military bases, constructed in the 40s and 50s, were scattered over large parts of the province. Lead mining in the Mendips was underway by as early as 49 CE and was exported as far as Pompeii.

The IInd Augusta moved westwards, establishing in the mid 50s a full fortress at Exeter. The IXth Hispania moved northward although the fortress at Lincoln does not date before c.60 CE. The XIVth Gemina, going northwest, probably in the late 50s based themselves in the fortress at Wroxeter (Shropshire). Finally, the XXth Valeria vacated Camulodunum in 49 CE, possibly moving to Kingsholm.

The following years were quiet, thanks in large part to the new procurator, a provincial named Gaius Julius Classicianus. His tombstone was found at London, suggesting that this city had become the provincial capital, probably because it had suffered less damage than Camulodunum and was better geographically sited. In 66 CE the province was sufficiently peaceful for there to be a vast legionary reorganization, involving the withdrawal of the XIVth, in Wroxeter, from the island. Glauchester was founded, probably for the IInd Augusta moving from Exeter.

The Flavian period (69-96 CE) was a time of the remarkable civil development of Britain, but the north and parts of Wales had to remain under military control. By the time of Hadrian in 117 there were indications of a new generation of warlike tribesmen in the north, which lead to the construction of Hadrian’s Wall.

The VIth Victrix was certainly one of the legions involved in the construction, brought to the island by Aulus Platorius Nepos, the emperor’s pro-praetorian legate, in 122 from his previous posting as governor of Lower Germany. Whether the IXth Hispania remained in Britain is uncertain. It is not attested in the province after 107/8 CE and may ultimately have been annihilated in the east in 161 CE.

Septimus Severus and then his son Caracalla campaigned extensively in southeast Scotland during that time. Severus died in York in 211, and Caracalla may have fought for another year before imposing peace on the Maeatae and the Caldonians.

The Severan campaigns in Scotland brought peace to Britannia for almost a century. Moreover, Britain was to largely escape the consequences of the third century crisis, when more than fifty emperors ruled between 244 and 284. However, evidence indicates a significant third century change in the military deployment in Britain. The standing garrison must have been greatly reduced by the constant demands for troops. By 300 CE there may have been fewer than 20,000 Roman troops in Britain.

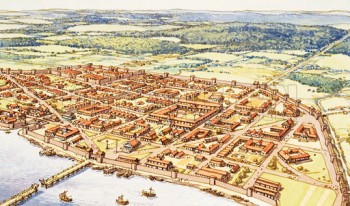

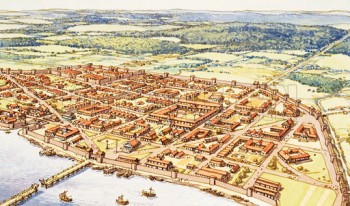

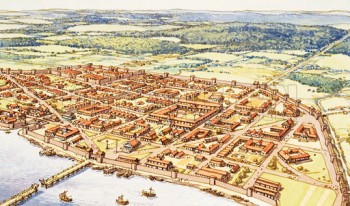

Development of Londinium

Londinium did not exist as a tribal capital when Julius Caesar explored it (probably crossing with his legions near the ford of what would become Westminster); it was not until after the Claudian conquest of Britain that the city was founded as a trading capital to serve the legions, circa 50 A.D. The settlement stood north of the river Thames (Thamesis), between two hills (Cornhill and Ludgate) in what is now known as “the city.” There was also a suburb in Southwark. Laid out in the typical legionary grid pattern, the city was approximately 62 acres in size and had become an important trading center by the time of the Boudiccan Revolt, when it was completely and savagely destroyed.

Rebuilding after the city was burned, a permanent legionary fortress was built to the west of the imperial city. From AD 61 onwards, there was a major building program, including the building of an impressive Imperial Forum and a later Forum (in the second century) that was nine acres in extent. The docks along the Thames suggest vibrant trading activity from Britannia to Europe, and Flavian docks were rebuilt that stretched longer than 330 yards along the riverfront. From 61 AD, Britain rated its own procurator, and a procurator’s palace was built that probably remained the headquarters of Imperial government. The governor’s guard and staff were seconded and lived here, drawn from other legionary units, probably in the fort near Cripplegate, built around 90 A.D. In the late second century, a great fortress gate surrounded the city, parts of which survive to this day, enclosing more than 330 acres. At the same time (and perhaps, due to disturbances that accounted for building the great wall), Londinium’s trade apparently suffered some decline, although luxurious townhouses continued to be built in the city. Roman Londinium was a cosmopolitan center, and had many beautiful public buildings. Besides the governor’s palace, there was a Mithraeum, an ampitheatre, large markets, luxurious homes, and all the trappings of Roman provincial luxury. The status of Londinium is unclear: it may have been, successively, a municipium and a colonia and may have served as a provincial capital in the Early Empire. By the early third century A.D., it was certainly the capital of Upper Britain, and was renamed Maxima Caesariensis under Diocletian. At some point, it was also named, simply, “Augusta.”

Dependent upon imperial trading culture, as Roman Britain became more threatened by Anglo-Saxon invasion in the fourth and early fifth centuries, Roman Londinium declined and was eventually abandoned after the Roman armies left Britain.