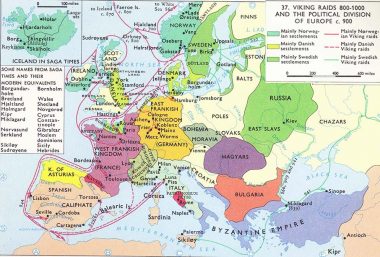

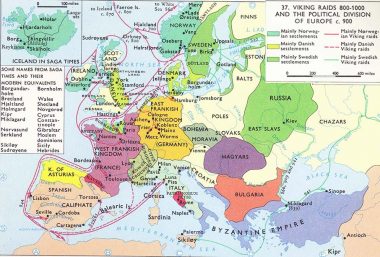

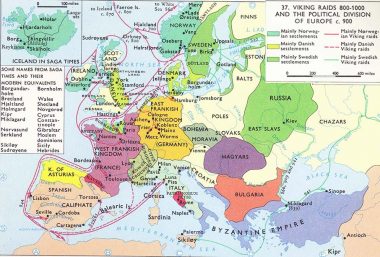

The reign of Charles the Great or Charlemagne is often referred to as a renaissance, a time when Western Europe sought recovery from the barbarian ravages that helped to transform Rome from an empire to a series of self-sufficient territories. These pagan ravages had not ended when Charlemagne was crowned King of the Romans by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day in AD 800. After Charlemagne died in 814, one of Western Europe’s most consistent threats came from the Vikings or Norsemen, Scandinavians known for plundering the British Isles and what was left of Charlemagne’s kingdom during the 9th Century.

Scandinavian Migrations Begin the Viking Age

The influence of the Scandinavians cannot be underestimated. Despite their usual depictions as pirate-types destroying churches and monasteries – a picture left by Christian chroniclers, their migrations and ultimate settlements are far more complex. Historians differ as to the reasons the Danes and Norwegians traveled south, often establishing agricultural communities and commercial settlements as in the Shetlands and Orkneys.

While there is always the side of adventure that paints the Scandinavians as freebooters and, if Christian sources are to be trusted, a “scourge” ripe for conversion, historians note population concerns that might have forced migrations as well as the early consolidation and centralization of rudimentary kingdoms in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. What is not questioned is the scope of these migrations.

Another reason involves changes in climate, forcing emigration to southern regions. Evidence of climate changes impacting emerging communities is growing and can be traced to far earlier periods. But migrations for a variety of reasons are still the accepted historical answer, according to Tierney and Painter.

Evidence of Extensive Migratory Patterns in the British Isles

Matthias Schultz, commenting on a highly controversial topic, at least in Britain, writes that, “Biologists at University College in London studied a segment of the Y chromosome that appears in almost all Danish and northern German men – and it is surprisingly common in Great Britain.” (Spiegel magazine, June 16, 2011) Schultz adds that, “New isotope studies conducted in Anglo-Saxon cemeteries produced similar results.”

In 2007 the discovery of a Viking “treasure hoard” in northern England attested to the Scandinavian’s commercial motivations as well as their migratory habits. (Archaeology, November/December 2007) At the same time, Historian Charles Haskins, writing in 1915, refers to the Scandinavian’s “monopoly” of sea power, made more successful by their vessels often called “dragon ships.” These same ships carried Vikings to Constantinople as well as to North America.

Motivations for Viking Presence in Western Europe

Did the Vikings come to destroy? Scandinavians sacked numerous communities including Hamburg and Paris in 845, but historians agree that the Vikings were great traders as well as colonizers. In the year 911, the Viking chief Rollo was granted Normandy. Military historians point to this action as one of last resort: it represented a feudal answer to the Viking problem by making vassals of one group in order to stop the incessant incursions of the 9th Century.

The British Isles, however, were another matter, notwithstanding the long-term influences of Germanic invasions. England had been part of the Roman Empire and was fully converted. Ireland evolved independently, without any political unity. Even the Irish Catholic Church developed differently without the presence of bishops. British historian H. R. Loyn argues that, “…the Scandinavians played a part, possibly a decisive part, in the making of England, of Scotland, of Ireland, and of Wales.”

Unlike Europe (Charlemagne attempted to pacify and convert the unruly Saxons three times during his reign), England was Christian. Charlemagne, in establishing the cathedral school at Aachen, looked to York for his principal teachers, monks like Alcuin. Not until the reign of Alfred in England, however, were the Danes checked and violence and plundering subsided, at least for a time. This threat would continue into the 11th Century.

Legacy and Historical Interpretations of Viking Incursions

The Viking Age (800 – 1100) was characterized by extensive migration, commercial pursuits, and a spirit of adventure. Loyn, for example, analyzes this quest for “status” as, “Possession of a free kindred, possession of land, and valor in war…”

Historical interpretations are also bound by national feelings. Thus, Jacques Le Goff refers to the Viking migrations in terms of plunder, while Norwegians strive to portray their ancestors in more enlightened terms. Visitors to the Viking Museum in Oslo, for example, will be reminded that it was a Norwegian who first discovered America, not an Italian sailing for Spain.

The Sophistication of Early Scandinavian Culture

That the Vikings were more than mere pirates is evident from their artifacts. The archaeological find at Harrogate, northern England included over 600 coins, some of which came from Russia and Afghanistan. At the Oslo Viking Museum, scientists discovered tools, textiles, and jewelry representing a sophisticated civilization along the banks of Oslo’s fjord.

Loyn, for example, discusses the construction of their sailing vessels as well as their superb navigational skills. Taken together, such evidence supports conclusions that the Vikings, according to Hastings, “had…a culture of their own…rich in its treasures of poetry and story.” Viking influences persist, and not just in Germanic fairy tales, the days of the week, or their colorful sagas.

The Scandinavian contact with Western Europe toward the end of the 8th Century was as much a contribution to western culture and traditions as the remnants of Rome and the growth of Christian institutions. Their migrations helped to alter existing societies, creating an added framework to the evolving culture that would become Western European civilization.

Sources:

- Charles Homer Haskins, The Normans in European History (Barnes & Noble, 1995; first published in 1915)

- Gwyn Jones, A History of the Vikings (Oxford University Press, 1968)

- Jacques Le Goff, Medieval Civilization 400-1500 (Basil Blackwell, 1988)

- H. R. Loyn, The Vikings in Britain (St. Martin’s Press, 1977)

- Matthias Schult, “The Anglo-Saxon Invasion: Britain Is More Germanic than It Thinks,” Spiegel, June 16, 2011

- “Spectacular Viking Hoard,” Archaeology, Volume 60, Number 6, November/December 2007

- Karl Theodor Strasser, Wikinger und Normannen (Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt, 1928)

- Brian Tierney and Sidney Painter, Western Europe In The Middle Ages 300-1475, Fifth Edition (McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1992)