The decisive battle of Philip’s conquest of Greece occurred in 338 BC at Chaeronea in Boeotia, when Philip beat the Athenians and their allies. The military feat that won that day was a cavalry charge by Philip’s eighteen year old son, Alexander. Alexander seems to have inherited much from his brilliant father: physical courage, arrogance, extreme intelligence, and, most importantly, unbridled ambition. For when his father died in 336 BC at an assassin’s hand, Alexander quickly consolidated his power and set out to conquer the world. At the age of twenty-one.

He had been a youth of infinite promise. Physically handsome, strong, brave, and nothing short of brilliant, he had been schooled by no less a person than Aristotle. With all these qualities, he took up his father’s ambition and prosecuted it with a swiftness that is almost frightening.

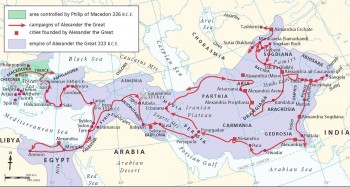

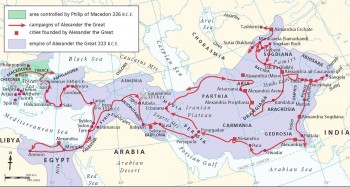

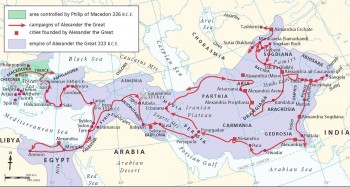

In 334 BC, Alexander (336-323BC) crossed over into Asia Minor to begin his conquest of Persia. To conquer Persia was to conquer the world, for the Persian Empire sprawled over most of the known world: Asia Minor, the Middle East, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran. He didn’t have much to go on: his army numbered thirty thousand infantry and only five thousand cavalry. He had no navy. He had no money.

Alexander strategy was simple. He would move quickly and begin with a few sure victories, so he could gain money and supplies. He would focus on the coastal cities so that he could gain control of the ports; in that way, the Persian navy would have no place to make landfall. Finally, he took the battle right to the center of the opposing forces, and he threw himself into the very worst of the battle. His enemies were stunned and his troops grew intensely loyal to this man who threw both them and himself right into the teeth of the wolf.

He quickly overran Asian Minor after defeating the Persian forces that controlled the territory, and after seizing all the coastal cities, he turned inland towards Syria in 333 BC. There he engaged the main Persian army under the leadership of the Persian king, Darius III, at a city called Issus. As he had done at Chaeronea, he led a astounding cavalry charge against a superior opponent and forced them to break ranks. Darius III, and much of his army in the The Battle of Issus, ran inland towards Mesopotamia, leaving Alexander free to continue south. Alexander seized the coastal towns along the Phoenician and Palestinian coasts. When Alexander entered Jerusalem, he was hailed as their great liberator. Alexender continued south and conquered Egypt with almost no resistance whatsoever; the Egyptians called him king and son of Re.

By this point, Darius III understood that the situation was out of his control. As Alexander moved down the Phoenican coast, he managed to conquer the city of Tyre, which was absolutely central to Persian naval operations. Darius III knew that he could never recover Asia Minor, Phoenicia, or Palestine, so he sent an offer to halt hostilities. If Alexander would cease, Darius III would cede to him all of the Persian Empire west of the Euphrates River; Mesopotamia, Persia (modern day Iran), and the northern territories would remain Persian.

Alexander would have none of this. In 331 BC, he crossed the Euphrates river into Mesopotamia. Darius III met him near the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh, the city that had been destroyed by the Chaldeans only three centuries earlier. In this last Battle of Gaugamela also called the Battle of Arbela (near today’s Mosul in Iraq) Persian army was almost completely defeated. When Darius’s army was already broken Darius III fled from the battlefield. In January of 330 BC, Alexander entered Babylon: he had conquered Mesopotamia and now controlled its greatest and wealthiest city.

The Persians had amassed vast wealth from the tribute paid by the various states under them. Alexander, who had started with no money at all, was now in control of the fattest treasury that had ever existed.

Darius III, meanwhile, met his death at the hands of a conspiracy. The Persian nobles no longer felt that he could effectively lead them and, under the leadership of his brother Bessus (also known as Artaxerxes V), the nobles killed Darius and left his body for Alexander to find. Alexander, however, pushed on, found Bessus, and killed him and as many Persian nobles as he could. The Persian Empire had officially come to a close.

Having conquered what was then the known world, Alexander had pushed his army to the very limits of civilization as he knew it. But he wanted more; he saw that the world extended further and partly out of curiosity, and partly out of a desire to conquer the entire world within the boundaries of the river Ocean (the Greeks believed that a great river, called Ocean, encircled all the land of the world), Alexander and his army pushed east, through Scythia (northern Iran), and all the way to Pakistan and India. He had conquered Bactria at the foot of the western Himalayas, gained a huge Bactrian army, and married a Bactrian princess, Roxane. But when he tried to push on past Pakistan, his army grew tired, and he abandoned the eastward conquest in 327 BC.

In 324 BC, Alexander returned to Babylon. He was now, literally, king of the world, and began to lay down his strategies for consolidating his empire. He began to plan cities and building works, new conquests, and even considered deifying himself. In 323 BC, at the age of thirty-three, he fell into a fever and died.

It’s rare in history that human events become so focused on a single individual; rarely is that focus justified. Alexander, however, is one of the notable exceptions. The age of Alexander was the age created by Alexander, and he would permanently stamp world culture with a Greek character. He was in many ways a brilliant and selfless person, quite possibly the most brilliant military leader in human history. With a small army, little or no supplies, and no money, he conquered the greatest, wealthiest, and most powerful empire in the world.

He never lost a battle, not once, and he flung himself into battle with intense physical bravery. He was also a tyrant and a bully, given to fits of uncompromising violence. He was certainly a drunkard and at times unstable. We will never know if he could have ruled or unified this huge empire, for it may have crumbled into nothing within a few years. His death, however, guaranteed that the empire he had built would never last.